Press releases

President Vahagn Khachaturyan delivered a speech at the “Academic City Armenia: International Knowledge Forum”

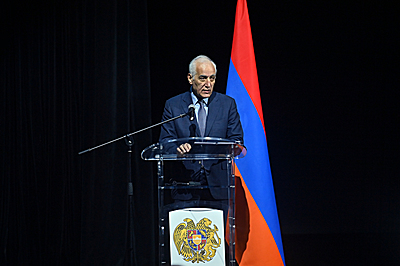

The President of the Republic of Armenia, Vahagn Khachaturyan, delivered opening remarks at the two-day conference “Academic City Armenia: International Knowledge Forum.”

Opening remarks were also delivered by Zhanna Andreasyan, Minister of Education, Science, Culture and Sports of Armenia, and Givi Mikanadze, Minister of Education, Science and Youth of Georgia.

President’s speech:

“Distinguished participants of the conference,

First of all, I would like to welcome all participants of the “Academic City Armenia: International Knowledge Conference.”

The title of the conference itself suggests that the main goal of the upcoming discussions is to examine the global challenges and innovative developments emerging in the fields of higher education and science, as well as to present Armenia’s strategic vision for advancing its role in the sphere of international education and research.

My remarks will briefly touch upon this year’s Nobel Prize laureates in Economic Sciences. The reason is simple: first, because the prize was awarded to scientists who have made outstanding contributions to the theory of economics—namely, to the theorists of what is known as “creative destruction”; and second, because it is directly related to technological progress and the link between knowledge and education.

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to three economists whose work embodies the idea of “creative destruction,” first introduced in the 1940s by Joseph Schumpeter. Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt expanded our understanding of how technological progress contributes to human development and the improvement of living standards. As Schumpeter described, “Every technological innovation has two faces: it destroys—rendering old methods obsolete—and it creates—flooding the market with new products and more efficient ways of meeting human needs.”

The Nobel Committee’s focus on creative destruction is particularly relevant today, in an era dominated by fears surrounding artificial intelligence. Public discussions often emphasize the destructive side of AI—the jobs it may displace or the industries it might transform beyond recognition. Far less attention is paid to its creative side — the emergence of new products and services, the efficiency that will make certain problems economically viable for the first time, and the opportunities that arise when resources are freed from old, less efficient uses.

I am confident that throughout the discussions, “Academic City” will naturally be at the center of many participants’ attention. In this context, I would like to recall the thoughts of Joel Mokyr, one of this year’s Nobel laureates and an economic historian: “Economic change depends, more than most economists think, on what people believe.” Beliefs and discourse, along with material transformation, constitute the missing piece in the puzzle of modern economic growth.

For Mokyr, an innovator is a kind of rebel—someone unwilling to accept the world as it is, determined instead to reshape it. Prosperous economies rely on innovation as their fuel, yet innovation itself depends on an institutional environment that welcomes such creative rebellion. Without openness to experimentation and dissent, even the most talented minds will lack the space to transform ideas into progress.

Meanwhile, Aghion and Howitt were pioneers of what macroeconomists call the theory of endogenous growth.

Unlike earlier models that viewed growth as driven by external forces such as capital accumulation or random technological shocks—Aghion and Howitt explored how innovation arises from within the system itself. To them, technological potential is nested within the institutional fabric of every society, like a chick developing inside an egg. Economies evolve or stagnate depending on how well they encourage or suppress creative destruction.

According to this year’s laureates, sustainable growth is not merely a matter of investment or research spending. It requires openness to technological change and the willingness to accept the instability it brings.

Governments must resist the temptation to yield to their internal Luddites. Luddites were members of the 19th-century English textile workers’ movement that opposed certain forms of mechanization over concerns about wages and product quality. They would often destroy machines during organized raids. These workers called themselves Luddites after the legendary weaver “Ned Ludd,” whose name was used in threatening letters to factory owners and officials.

Excessive regulation and patronage policies can stifle entrepreneurial experimentation, hinder investment, and ultimately suffocate creativity. Limiting the influence of vested interests seeking protection from competition is equally vital. When established firms dictate the political agenda, they often do so at the expense of innovators who may one day replace them.

Once again, I would like to emphasize that this year’s Nobel Prize is a rare and well-deserved tribute to those who have deepened our understanding of the dynamics of innovation, institutions, and creative destruction. By honoring them, the Committee reminded the world that economic progress depends not on avoiding change but on harnessing it.

And it is precisely this philosophy that must guide us in the coming years, especially as we seek to solve strategic challenges and confront difficulties in the field of education.

Education, knowledge, creative destruction, and new technologies are the driving forces that will ensure the continued development of the Republic of Armenia, the well-being of its citizens, the growth of its economy, and the strengthening of its national security.

I wish you all productive work.”